It’s a well known fact that the Celts – and later the early Christians – in Ireland were extraordinarily creative people, regularly expressing their philosophies, beliefs and histories through art. At first this was done through stone carving, metalwork and most likely wood. Celtic society revolved around the concepts of war and wealth, so they spent much of their time creating intricately decorated weapons and jewellery from bronze and gold, to show off their fighting prowess and status in society. They were also a highly spiritual society with an astronomical and seasonal calendar, various ritualistic festivals throughout the year, and revered burial practices. At sites where these ceremonies took place stone monuments were very common and often featured elaborate carvings, sculptures and the like.

Later as their skills and literacy developed and as Christianity was introduced to the country, this expression transferred to finer arts like painting and illuminated manuscripts such as the famous Book of Kells, and was used to teach the masses about religion. The old skills of metalwork and stone carving were not forgotten however, but were just used in different ways. Instead of jewellery, objects for religious ceremonies such as chalices, croziers and shrines were crafted, and instead of stone monuments to bury the dead, large objects were sculpted and used as teaching aids or meeting places – the most important example of these is the High Cross.

Origins of High Crosses

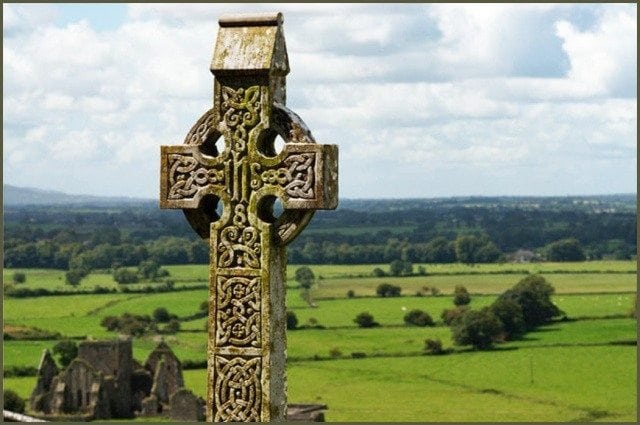

A high cross is exactly what you may think given the name; a very large, high cross! There’s no definitive proof on where they originated, but it is generally thought to be either in Ireland or Britain. A likely scenario is that wherever they originated, travelling missionaries took the concept with them and they spread across the water that way. In any case, the best surviving examples are in Ireland and Britain, although some have also been found in Scandinavia, likely brought over by Viking settlers who had interacted with Christian culture. Irish crosses were the biggest and most elaborate than in any of the other countries, leading them to adopt a distinctive design – the four arms of the cross were encircled in a ring. This arguably has some symbolism to it regarding eternal life, but it’s much more likely that because the cross was so large and heavy, the stonemasons added it in to provide extra support for the arms.

Historians can’t place an exact date on when high crosses first started to appear in Ireland. The oldest surviving stone examples date from around the 8th and 9th centuries, but it is entirely likely that there were wooden versions around before this, probably decorated with metal plates or carved. They were likely a carry-on from the old Celtic practice of placing stone monuments in important or sacred places, and their functions would have been similar in many ways too; to serve as a meeting point, a focal point for ceremonies, to mark boundaries, or to declare a territory as being Christian. Unlike their predecessors however, they were not used to mark burial places and were never used as headstones (although there are some headstones in the shape of high crosses, these date from much more modern periods and are a deliberate homage to the earlier monuments).

The natural location for the vast majority of high crosses was on the ever increasing number of monastic sites popping up around Ireland at the time. The typical layout of these early monastic sites was a church and a round tower (a defensive measure to survive Viking sieges), facing each other and a short distance apart, with the cross situated in the middle of the two structures. Most of the stone churches were too small to accommodate the large gatherings of worshippers who turned up, so ceremonies would have been held outdoors around the cross instead. This also left them more prepared in the event of a surprise raid by the Vikings, so in short, the high cross was a fairly good addition to the country!

Construction and Decoration

High crosses would have been constructed by stonemasons skilled in their craft, living and working in the monasteries. They were usually built in three parts – first, a conical or pyramid shaped base with a hollow centre; second, the cross itself, the shaft of which was slotted into the hollow centre of the base. Lastly, a capstone was added on top, although very few of these survive today. The average height was around eight feet, but there are examples in Ireland up to three times that height. The cross was always placed in situ before the carving work was completed. This was done to save time and effort for everyone in case, for whatever reason, the cross decided not to stay erect and fell to the ground, ruining hours and hours of painstaking artistry.

Once erect, the masons would come in and complete the necessary carvings. It is also quite likely that they were then painted in bright colours, to make certain features and figures stand out and to improve the appearance of the stone overall. There is plenty of evidence of ancient Greek marble temples being painted, as well as Byzantine statues, so it’s a fair suggestion to make that high crosses could have been painted too, although there is no definitive proof either way. One replica high cross in the Irish National Heritage Park near Wexford has recreated a painted version, which most people agree looks extremely strange!

The first examples of high crosses in Ireland were decorated in typical Celtic insular art fashion; interlacing patterns, celtic knots, vine scrolls, and so on. Later on however carved figures were introduced to represent certain passages and stories from the bible. Starting small in size and sparse in number, as the centuries passed the crosses became larger and larger allowing more room for more carvings. While at first there may have just been a solitary figure of Christ in the centre, at the height of their use high crosses would have been covered head to toe in intricate pictorial representations of bible stories, to enable the priest to better illustrate his words when presiding over ceremonies. Ogham inscriptions and the names of the commissioners of the crosses were also often engraved along the base.

Irish High Cross Examples

Ireland has over 30 surviving examples of high crosses from various dates and with varying decorations. Here are some of the most historically significant and impressive examples;

Muirdeach’s Cross, Monasterboice, Co. Louth: regarded as the most beautiful example of Celtic stonework in existence, Muirdeach’s cross in the ruins of the abbey at Monasterboice stands 19 feet high, dates from the 10th century, and is constructed from sandstone. Each side is covered head to foot with almost 50 decorative carving panels with 124 different figures depicted and 17 different spiral, interlaced, and key patterns. In the centre of the front of the cross is a carving of the last judgement (which contains 45 different figures alone), while on the other side is the crucifixion. Just about every other well known bible story is also featured somewhere on the cross, including David and Goliath, Adam and Eve, and Cain and Abel. The ‘Muirdeach’ who commissioned the cross could have been one of three people; two highly distinguished abbots of the monastery or a king whose territory included the site.

Clonmacnoise Cross, Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly: Otherwise known as the Cross of the Scriptures or King Flann’s cross, the first historical record of the high cross at Clonmacnoise dates from 957 and it was likely in existence for a few decades before then. This cross is also decorated on all four sides and from top to bottom, with especially stunning interlacing patterns along the ring. It’s front panels depict the story of the crucifixion from the arrest of Christ at the bottom to the crucifixion itself in the centre. On the other side is the last judgement, and elsewhere panels depicting riders, chariots, Christ with Peter and Paul, and plenty more that are open to interpretation. The inscription on the bottom reads ‘A prayer for Colman who had this cross erected on behalf of King Flann’.

Ahenny Cross, Ahenny, Co. Tipperary: Ahenny actually has two high crosses, made of sandstone and standing around 3.5 metres high. Both are thought to be two of the earliest surviving examples in Ireland, dating from around the 8th or 9th centuries. As such they are mostly devoid of carved figures unlike the previous two crosses, and instead feature truly beautiful Celtic artwork on all sides. The bottom panel contains spirals while each arm of the cross is covered in highly detailed interlacing patterns varying in size and shape. There are also five high-relief circles on each arm and in the centre. The base panel of the later cross depicts some primitive figures including hunting scenes, the fall of man and Daniel in the Lion’s den.

Nether Cross, St. Canice’s Church, Dublin: Although not as impressive as the other crosses in this section in terms of decoration, the Nether Cross in Finglas, Dublin, nonetheless has an interesting story. Another early high cross example, it stands around 12 feet high and was constructed from granite, although much of its carving detail has now been weathered away. It must have once been held in high regard by the local parishioners however, because in 1648 when Oliver Cromwell came from England with his army to conquer Ireland, the villagers buried it and kept the location secret for some 150 years. In 1816 the reverend at the time heard the story from one of the few parishioners who still remembered the secret, and took it upon himself to unearth the cross and put it back where it belonged.

Ardboe Cross, Cookstown, Co. Tyrone: The Ardboe high cross was the first high cross erected in Ulster, dating from the 9th or 10th century. It the tallest and best preserved cross in Ulster, standing at around 13.5 feet high. It contains 22 panels depicting scenes from both the Old and New Testament including the early life of Christ on the north side, his miracles and crucifixion on the west side, Adam and Eve and the last judgement on the east side, and David and Goliath and Cain and Abel on the south side.