If you went to school in Ireland, have read any Irish fairy tales, or even visited any of the many ancient sites that are now tourist attractions around the country, you will by default know an awful lot about Irish mythology. The majority of Irish children will be able to tell you word for word of the tales of Tir na nOg, the Children of Lir, Cu Chulainn and Fionn MacCumhaill, and while they may seem like little more than fairy stories in that context, they are in fact important mythological tales that have been passed down for generations all the way back to the time of the ancient Celts.

Irish mythology is fascinating, dramatic and full of war, romance, magic and mystery. It has inspired much of modern Irish art and forms a big part of the Irish identity, but for the most part it remains either a random collection of old stories from school days, or a complicated web of characters, cycles and historical contexts. With that in mind, here is a general guide to Irish mythology, along with its main cycles, characters and stories, to help you make sense of it all.

How did Irish mythology begin?

Like most things Irish, it all started with the Celts. This band of tribes, warriors and farmers originated in the central European Alps, and spread out to occupy almost the entire European continent long before the ancient Romans became such a dominant force. At the peak of their power, they had inhabited everywhere between what is now Ireland in the west and Turkey in the east.

Around 225 BC, the Celts suffered their first major defeat at the hands of the Romans, and over the next few centuries more attacks came. Since they had no form of centralised government or organisation (they were each separate tribes who operated independently, only bound by language, customs and religion), they gradually declined. Except, that is, for the areas where the Romans and other societies never managed to reach; namely Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, Wales, Cornwall in England and Brittany in France. Celtic society was rich and complex. They placed great emphasis on war and victory, and viewed nobility, religion, wealth and beauty as hugely important. They were skilled craftsmen and created exquisite jewellery and decorative objects from gold, copper and bronze. They had an astronomical calendar and celebrated various festivals in honour of their gods and goddesses, constructing impressive monuments and tombs to honour their dead that were aligned with the stars.

Nature was also important to them, with trees, animals and the natural elements considered sacred. However, despite all of this obvious intelligence, there is no evidence of them using any form of writing apart from a primitive line script known as Ogham. They were almost entirely an oral society, passing their knowledge and skills through the generations through word of mouth and demonstration.

For that very reason, it is only through other sources that we have come to know the mythology of the Celts. The first mentions come from Roman sources, although since the Celts and the Romans were mortal enemies, anything written down by them was done so with an air of derision rather than an attempt at recording or understanding the complex stories. It was only when the first Christian missionaries came to Ireland and began converting the remaining Celts that some forward thinking monks began collecting the stories and writing them down, both for posterity’s sake and most likely to use as a tool for understanding the society in order to win them over to the Christian way of life.

As the stories passed down from generation to generation and then later to the monks, elements of them were lost, added to, misunderstood, and so on, further developing the stories into the vast lexicon we have now gathered today.

Cycles of Irish mythology

Irish mythology can be divided into four main cycles, in chronological order. Within each cycle there are many different stories and characters, some important and some not so important, but all regularly occurring. In many cases the stories also interweave with one another, making it even more confusing! The four main cycles are:

Mythological Cycle

The Mythological cycle is the earliest one, and recounts the tales of the Tuatha de Danann or ‘people of Danann’, who were the mythological descendants of the Goddess Danann, the ancestors of the Irish Celts, and the first people to inhabit the island (allegedly). The Tuatha de Danann were demigods, stunningly beautiful and expertly skilled in music and the arts, with magical powers to boot. The mythological cycle is largely concerned with how Ireland first came to be inhabited and the various struggles for ownership that ensued. The Tuatha de Danann were led to Ireland by a woman named Cesair.

Soon after they arrived a great flood wipes them all out except for one lucky survivor, Fintan. Fintan oversees the later settlements in animal form, the first unsuccessful one led by Partholan, and the second led by Nemed. Nemed’s settlement breaks up into three groups, one of which leaves Ireland. The other two, the original Tuatha De Danann and the Fir Bolg, spend many years fighting before eventually learning to live in peace.

The drama doesn’t stop there, however. Another band of warriors, the Fomoire, turn up to cause trouble, leading to two Gods arising from the Tuatha de Danann. One is Lug, master of the arts and warfare; the other is Dagda, the great God with a magical cauldron. The Fomoire and Tuatha have a huge battle known as the Second Battle of Mag Tuired. The Tuatha are victorius, but only until yet another tribe, the Sons of Mil, come along. The Sons of Mil are said to be the immediate ancestors of the Celts, and won the land by vanquishing the Tuatha to the underworld, where they now rule over the fairies.

Ulster Cycle

Up next is the Ulster cycle, the stories from which are much better known than the Mythological cycle. They focus on the warriors of King Conchabar, one of whom is known by everyone in Ireland: Cu Chulainn. Cu Chulainn is more or less the main character of the Ulster cycle, and all of the stories of his life are recounted. However, the Cu Chulainn in the mythological texts is not quite the same as the one from children’s stories. While he is an athletic man and the ultimate warrior, he also has a number of more grotesque features when he heads into battle; he grows in size, one eye rolls back into his head, his hair stands on end with drops of blood on the end of each hair, and he attacks anyone in the vicinity regardless of whether they’re a friend or an enemy! Some versions also claim he transforms completely into a non-human beast.

Another prominent character is Deirdre, whose tragic tale has inspired many modern Irish writers and creative types. She was unwillingly betrothed to King Conchobar, but instead fell in love with one of his warriors Naoise and escapes. When captured, she smashes her own head against a rock because she would rather die than be apart from her true love. The most famous story however is that of the Tain Bo Cuailgne, or Cattle Raid of Cooley, which features the ferocious Queen Medb. She raises an enormous army to raid the Cooley peninsula and steal the king’s most prized bull for herself (in those days, wealth was measured in cattle). The Ulster cycle differs from the other cycles in that it is the only one that has no mention of a centralised hierarchy of kings or government, and involves many unrelated stories of warring small tribes and regions.

Fenian Cycle

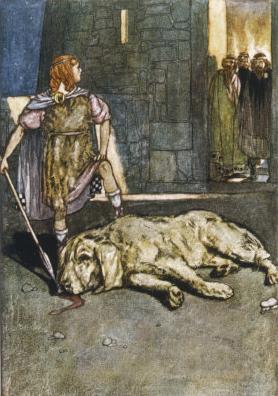

The Fenian cycle is the third cycle of Irish mythology, and is largely focused on the legendary warrior Fionn MacCumhaill and his band of loyal followers, the Fianna. While the Mythological cycle is based on the ancient gods and the Ulster cycle on the various conflicts between different regions, the Fenian cycle is all about the cult and institution of warriors. It starts off with the origins of the Fianna, formed by the High King Cormac MacAirt with warriors from each clan in order to protect his kingdom. One of the most significant leaders of the Fianna, Cumhal, is brutally killed, and his wife flees to a safe place in order to give birth to his son in secret (she feared he would be chased down and murdered too if anyone knew of his existence).

The son was Denma, later nicknamed Fionn because of his bright blonde hair. The rest of the cycle charts the various events of Fionn’s life, including his avenging of his father’s death, his time studying with the poet Fin Eces. There he accidentally eats the magical salmon of knowledge and gains all the wisdom of the world, and is admitted to the court of the High King of Tara after rigorous tests. He quickly impresses everyone and is made leader of the Fianna after he saved everyone from a malicious goblin who had been terrorising them at a big feast every year. He also met his wife, who had been trapped inside a deer’s body by an evil druid, until she turned back into a fawn again after giving birth to their son, Oisin.

From there, the cycle gets more and more interwoven with other stories, and becomes much too complicated for a simple summary! After a series of events, a huge battle at Gabhra culminates in the death of Fionn and the majority of his followers. Fionn’s son Oisin is among the survivors.

Historical Cycle

The final cycle of Irish mythology is the Historical cycle, which deals with the institution and founding of great and lesser kings of Ireland. This cycle was written by the bards of the king’s courts and blends mythology with historical detail. The main characters range from the almost entirely mythological Labraid Loingsech to the entirely historical Brian Boru, and include many other familiar characters.

This cycle dates from after the coming of Christianity and Saint Patrick, and so has been influenced much more by Christian teachings than the other cycles. Some of the most significant characters in the Historical cycle include; Cormac Mac Airt, founder of the Fianna, who’s dramatic life takes up a large portion of the cycle; King Conn of the Hundred Battles, founder of Connacht who was famous for his fighting prowess and for making the coronation stone of Tara roar when he stepped on it (meaning that he was Ireland’s rightful ruler); and Niall of the Nine Hostages who was the ancestor of the powerful O’Neill clan.

His nickname comes from a particularly tense battle when he took 9 hostages, one from each province of Ireland as well as one from the Scots, Saxons, Britons and Franks. His legacy has endured right up until today; O’Neill is still in the top 10 most common surnames of Ireland. Although there are probably thousands of separate stories, characters, and themes featured throughout each of the four cycles, the above is a small taster of what Irish mythology is all about.